Today, the acronym NIMBY is frequently used derisively to suggest a contradiction in desiring the benefits of progress, so long as any apparent adverse effects are ‘Not In My Backyard’ or ‘close to me’. But, ‘my backyard’ obviously expands beyond one’s own personal property boundaries. For some, the spatial dimensions of the broader region over which each person has a sense of ownership and caring has tended to expand over time. For colonists, first there is expansion in dominion[1], with a deeper sense of caring for the adopted landscape coming later. In the early period of colonial Australia, major developments were actively shunted from more populous areas to ‘backyard’ or out of sight areas, on the fringes of more developed areas. There, they could (temporarily) remain out of sight and out of mind. Unfortunately, this caused much damage to those fringing areas before their full suite of values could be realised. As the population grew there was inevitable expansion into the former fringes that were impacted by legacies of past practices.

First Peoples' artwork, photograph by Alan Fairley, Oatley Flora and Fauna Conservation Society Inc. Location Oatley Park

First Peoples' artwork, photograph by Alan Fairley, Oatley Flora and Fauna Conservation Society Inc. Location Oatley Park

Waterways and colonisation

Waterways played a central role in colonisation. Indigenous people living on these rivers had used them for millennia for easy canoe movement and productive harvesting. Yet these rivers also allowed rapid penetration by colonisers. The easy navigability of waterways allowed colonial expansion, but the waterways themselves then suffered the consequences of that expansion. For instance, the peak in intercontinental colonisation was dependent upon travelling across oceans in ships. New colonies could only be established in areas with an accessible and dependable supply of freshwater. Despite the importance of water, early colonists often turned their backs on waterways, which were used as dumping grounds, owing to the ability of water to wash some pollutants away. Such practices were inevitably environmentally unsustainable. Earlier generations were unwittingly eroding the capacity of waterways to provide values including amenity and recreational opportunities to the growing populace. Botany Bay is one waterway that suffered considerably by being considered Sydney’s backyard from the early colonial period. The rivers and creeks that flow into the bay have been impacted to varying extents.

NIMBY has no place in traditional Aboriginal land management

As for the rivers and creeks that flow through it, the history of human occupation and land use in the Botany Bay and Georges River catchments is diverse, long and winding. Aboriginal people of the Sydney region have lived in these catchments for millennia, with Botany Bay itself called Kamay Bay by local Aboriginals. The ample evidence that they regularly and sustainably used waterways over such timeframes includes artifacts such as oyster shell middens and rock art along waterways. Conversely, there are no legacy artifacts to suggest that Aboriginals were living unsustainably, which traditional Aboriginal culture actively works against. NIMBY has no place in traditional Aboriginal land management: with Connection to Country, all land is valued and used sustainably. Also found within the Botany Bay catchment were dugong bones with marks reflecting that the animal was butchered, presumably by Aboriginals for food. The bones were approximately 6000 years old. The presence of an animal that requires warmer conditions that those of present-day Sydney and the position of the bones also provided evidence of ongoing changes in the regional climate and sea level. Climates and landscapes do change over long timescales, but it is wrong to conflate these long-term fluctuations with the far more rapid changes of recent times. Native flora and fauna can evolve and adapt to long-term changes, but not the more rapid changes that occurred after European colonisation of the region.

Sydney Cove more suitable for establishing settlement

European colonisation of the region was set in motion in 1770, when the crew of the Endeavour sailed across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and landed on Kurnell Peninsula. They named the bay in acknowledgement of the high botanical diversity on the peninsula, having collected 132 novel plant specimens from the area during only eight days of surveying. They sailed back to Britain with the recommendation that the bay was suitable for the initial establishment of a new colonial settlement. Of course, the whole reason for that settlement was to move convicts from overcrowded British prisons: soon after, America refused to keep accepting convicts. Britain, then America, decided they didn’t want the convicts in their backyard, which heightened the need to find an alternative. In 1788, the eleven ships of the First Fleet, with their convict cargo, set sail for Botany Bay. However, when they arrived in the bay they could not reconcile the favourable recommendations with their own assessment that the bay was too shallow and windy to facilitate safe navigation and docking of their ships. The distribution of water across land was also unfavourable for settlement: much land was too damp and swampy, whilst they simultaneously could not find a body of extractable surface water to adequately supply the colony. Thus, the distribution of water was a major factor in their decision to pull up their anchors and set sail for Sydney Harbour. They judged Sydney Cove as more suitable for establishing the settlement, largely owing to how water sat in the landscape. The cove offered sheltered docking that was close to land and the Tank Stream provided a supply of freshwater.

https://maps.six.nsw.gov.au

https://maps.six.nsw.gov.au

Backyard of the colony

Changing the location for initial settlement was a fateful decision for the whole region. For Botany Bay, it was the decision that both delayed the initial onslaught of intense development, but also made it the ‘backyard of the colony’. Since that time, activities thought too unsightly and/or polluting for the more populous Sydney Harbour were frequently moved into the Botany Bay backyard. The northern shoreline of Botany Bay suffered multiple insults. The underappreciated swamps were ultimately ‘reclaimed’ to support major developments, such as the airport and seaport. Across the broader landscape of the Botany Bay and Georges River catchments, historical land use decisions have created the present patchwork of urbanisation, intense industrial development and protection.

Resources extracted

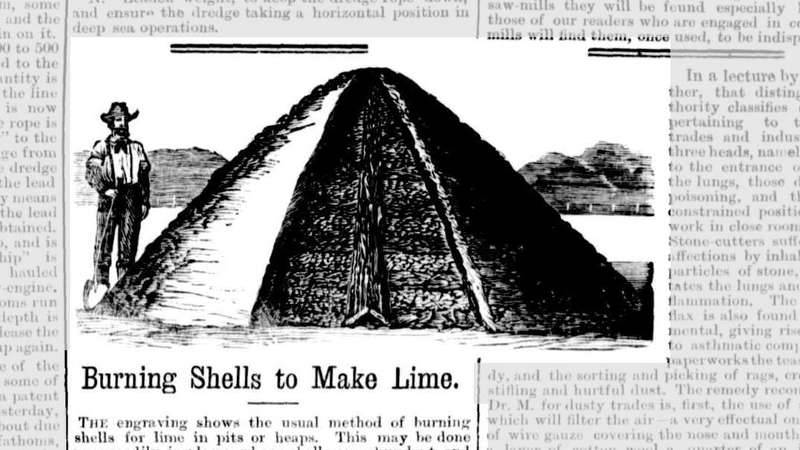

The Georges River is the largest river that flows into Botany Bay. In 1795, Bass and Flinders surveyed and named the river after King George III. The river may have previously been called Tucoerah by local Aboriginals, but it is unclear whether this was the name for the whole river or just a part. Resources were being extracted from the broader Botany Bay catchment to fuel the main development on Sydney Harbour by the early 1800s. This included fish for sustenance and oysters for both food and building. In fact, shellfish were the key binding ingredient for the early colony. The colonists found that the local hardwood timber damaged their saws and axes, so rather than use timber they used stone for construction. That required mortar, which required lime. There were no geological limestone deposits along the coast, so the colonists extracted it by burning seashells in lime kilns.

Noxious industries moved out of sight from Harbour

Inland from the bay, large areas of forest that existed on rich soil were cleared for farming, which was the most common initial land use by colonists. But, the shorelines around the bay, which featured sandy soil and saline water and were not as suitable for farming, were used to accommodate polluting industries including ‘sewage farms’, tanneries, breweries, quarries, candle makers and soap manufacturing. Surrounding environments had resources extracted and pollutants imported. For a short period, there were also grants for aristocrats to establish large country estates, but by the early 1830s land grants were replaced by land purchases. This was a time of rapid colonial progress and expansion. Sewage and industrial effluents were legally discharged to waterways. There was a push to develop more satellite towns around Sydney. Liverpool was the first large town built on the Georges River in 1810. In 1836, convict labour was used to build the weir to capture the town’s water supply. A small dam was also built across the Cooks River in 1840. The need to find new water supplies to support colonial expansion led to proposals for larger dams on both the Cooks River and Georges River. In the Georges River, there was the very ambitious suggestion to build a dam near the river mouth, where Tom Ugly’s bridge now crosses the river. Those damming projects were shelved, with the Woronora Dam built in 1927 instead. But, development continued unabated. By the late 1800s, railways and tramways made the lower Botany Bay catchment far more accessible than previously. This facilitated rapid expansion of residential development, heedless of the emerging consequences of overzealous extraction. Concurrently, in 1883, a Royal Commission advised that Sydney’s noxious industries should be moved and concentrated out of sight from the growing population on the Harbour, on the northern side of Botany Bay. That site subsequently became the most polluted metropolitan location in Australia.

Landscape radically transformed

Uncontrolled extraction led to the almost complete depletion of natural oyster stocks in the Georges River. This prompted the development of laws and establishment of the oyster cultivation industry in the river, with the first successful farming operation beginning in 1886. So began one of Australia’s earliest recorded aquaculture ventures. Uncontrolled harvesting of natural oyster reefs and fish was increasingly being recognised as unsustainable, with the beginning of some coordinated efforts to counter this. But, by the turn of the century, the whole landscape had been radically transformed and the pollution emanating from across the catchment was becoming an increasing threat to maintaining fisheries and other values of the river. Organic pollutants including sewage discharged directly to rivers was smelly and harmful to human health, but eventually decayed. This is in contrast to the inorganic pollutants that accumulate in sediments, rather than decay, and which were becoming more prevalent in the Botany Bay catchment in the 1940s. The earlier lessons of impacts of overharvesting fisheries were not heeded as new machines created the ability to extract other resources. Huge amounts of sand were mined from the upper Georges River estuary and Kurnell Peninsula. So much sand was extracted that a large part of the former channel was transformed into lakes, called Chipping Norton Lakes. The sand dunes behind Lady Robinsons Beach were also flattened, in some cases by filling depressions between crests with rubbish. Across the estuary, the heavy machinery made it increasingly possible to ‘reclaim’ land previously covered by undervalued intertidal marshes. Garbage, landfill and dredge spoils were dumped to build shorelines up above the high tide level, often at the expense of saltmarshes and mangrove. Large swathes of seagrass were also destroyed via dredging and siltation. Only relatively recently has the importance of those habitats to fish become appreciated.

Shorelines altered

Construction of the oil refinery, airport runways and seaport massively altered the landscape around the shorelines of the bay from the 1950s. The Kurnell oil refinery was built in 1955. The airport construction had a major direct impact on waterways. It was built directly on top of the Cooks River, with the lower reaches becoming highly engineered and the mouth of the river being shifted 1.6 kilometres away from where it previously flowed to the bay. From 1959, runways were extended into the bay to accommodate the airport expansion. By 1962, the toll from land use intensification on the Georges River was reflected in the middle reaches of the river being closed for swimming. Around the same time, Sylvania Waters was being developed in the lower Georges River, inspired by canal developments of the Florida Keys and the first of that genre in NSW. By the late 1960s, the seaport functions of Sydney Harbour were becoming constrained with the rising population, which again looked to their backyard and construction of Port Botany began in 1971, just prior to more stringent environmental restrictions being enacted. Around the world, there was an uprising against uncontrolled environmental destruction, with associated losses in biodiversity and the ability of humans to enjoy the aesthetic and recreational opportunities previously provided by unpolluted ecosystems. By the 1970s, environmental laws were improving and the predecessor to the Environmental Protection Authority was formed in NSW. The uncontrolled discharge of pollutants into waterways based on the thinking that ‘the solution to pollution is dilution’ was no longer acceptable. However, this is not to suggest there isn’t ongoing smaller scale licensed and unlicensed polluted discharges into waterways.

Wave refraction changed

The airport and seaport required the physical transformation of the bay through reclamation of 600 ha of land that was formerly largely swampy, extensive dredging to allow passage of cargo tankers, plus reconfiguration and hardening of shorelines. These hardened shorelines changed wave refraction across the bay, requiring building of breakwalls and groynes to try to counter the erosion of sandy shorelines. That remains an ongoing battle. Another major issue with international seaports is that arriving ships can bring in exotic species on their hulls and in ballast water.

Since mid-1970s

Over the past half of a century, since the mid-1970s, the Botany Bay and Georges River catchments continued to experience environmental wins and losses. Coal mining operations began in the upper catchment in 1976. Towra Point was recognised as a Ramsar wetland of international significance and afforded commensurate protection from 1985. The oyster industry was decimated by QX disease in the mid-1990s then Pacific Oyster Mortality Syndrome in 2010. Commercial fishing ceased in 2002. From the 1990s, councils across the catchment increasingly implemented Water Sensitive Urban Design (WSUD), which is intended to counter the detrimental impacts of urbanisation on waterways. There are wonderful examples of WSUD infrastructure scattered across the catchment. This is in recognition that the vast majority (> 85%) of local waterborne pollutants are discharged in urban stormwater. Sewage pollution continues to hinder recreational uses of the waterways. Oil spills became less prevalent. Between the late-1950s and 1980s there was an average of at least one oil spill each year in the bay, although it is likely that many spills were unreported. Large oil spills do attract much attention from the media and public, although their pulsed impacts are less severe than the ongoing and more insidious pollution from stormwater. There have been recent large developments along the Georges River, such as the expansion of Warwick Farm Racecourse and the Moorebank Intermodal. Local people have increasingly joined efforts to clean litter from waterways and it was a group of volunteers that initiated the formation of Georges Riverkeeper in 1979. Many other groups that care about the local landscape emerged, including Botany Bay and Catchment Alliance, Cooks River Alliance, Georges River Environmental Alliance, Menai Wildflower Group, Mudcrabs, National Parks Association, Oatley Flora and Fauna, and Sutherland Shire Environmental Centre.

Most recently

For the past decade, River Health Report Cards from Georges Riverkeeper and Cooks River Alliance have shown that the urban creeks that flow into the rivers have poor condition. Some people ask whether the grades have improved over time. The sad truth is that they haven’t, as can be seen in the latest State of the Georges River Report. The legacies from past poor land uses continue to haunt us. Further, it isn’t easy balancing maintaining river health in a catchment as highly urbanised as the Botany Bay catchment. Waterways continue to be subject to many of the pressures that are common to urbanised regions around the world, including deforestation and habitat loss, high stormwater flows, poor water quality, sewage, litter and exotic species. Climate change will exacerbate the impacts on biodiversity and livelihoods. Our own decisions on trade-offs will continue to present challenges. For example, the Woronora Reservoir in southern Sydney continues to provide drinking water, but there has been a recent decision to allow mining under the reservoir: it is questionable whether those uses are compatible. The lack of improvement in waterway condition is not from a lack of trying. Around the world, there are efforts to improve the management of urban rivers and there are some fantastic projects occurring locally. Fortunately, some waterways in the Botany Bay and Georges River catchments continue to maintain high conservation values and are minimally disturbed. The area has four National Parks: Kamay Botany Bay NP, Georges River NP, Dharawal NP and Heathcote NP. Sandstone ridges, which are challenging to develop, and the Holsworthy Military base, have provided protection to large patches of forest in the south of the Georges River catchment.

Current planning

Achieving sustainable management is an ongoing challenge, involving trade-offs between conflicting uses. Sustainable management includes the principle of intergenerational equity – essentially, legacies of our actions should not diminish the suite of valued uses of land for future generations, whether that land is currently highly valued or on the fringes. The Botany Bay and Georges River catchments are no longer just Sydney’s backyard, with over one and a half million residents, including one of the largest populations of Aboriginal people in Australia. Property values around the bay provide a testament of the premium on the amenity values offered by the bay itself. Yet, there remains a modern version of the denigration of Sydney’s southern fringe areas, with the implication that they can carry more of the burden not wanted in more affluent areas, within the concept of Sydney’s ‘Latte Line’ or ‘Red Rooster Line’. There is a grand vision for Sydney to become a metropolis of three cities, with surges in the population of Greater Parramatta and the Western Sydney Aerotropolis, the first of which is intersected by these lines and the later clearly relegated to the less affluent side of those imagined boundaries. Such a vision cannot be achieved by continuing to think of some areas as satellite ‘backyards’ where undesirable activities can be displaced. Changes to the way that we manage water has greatly improved the cleanliness of Sydney Harbour, whilst residents of the eastern city also have access to clean beaches along the coast, which have always had the benefit of tides and waves to sweep away pollutants. Fortunately, as we embark on this latest developmental surge, there is recognition that southern and western Sydney will require access to well-watered environments to avoid turning the new urban centres into unbearable heat islands. Current planning has the stated aspirations of protecting and improving the condition of coasts and waterways, preserving their biodiversity values, enhancing vegetation along waterways and protecting scenic and cultural landscapes. If we do this, local waterways will continue to provide multiple values. This will add to building communities that have a deeper sense of caring and connection to the newly created urban centres. We should learn from the lessons of the past, including from Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge, and consider whether there are alternatives or ways to mitigate the impacts of those human activities that we would not accept in our own backyards.

[1] In Australia, it must be acknowledged that sovereignty was never ceded by Aboriginals.